Interrogating the Format: Subversions of Presentation and Playback by Industrial Musicians

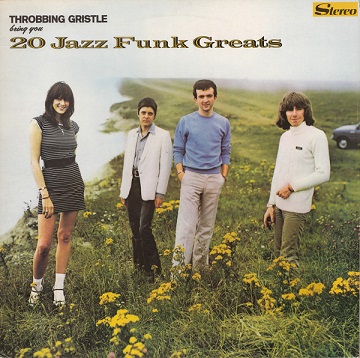

Look at any list of the greatest Industrial albums ever released, and you’ll always find the same entry at #1, Throbbing Gristle’s infamous 1979 release “20 Jazz Funk Greats”. Even to those who have never heard the record, its reputation precedes it, not only for its musical content, but also its intentionally misleading presentation.

Needless to say, the album is not Jazz-Funk, nor is it comprised of 20 tracks. The only part of the title that holds any truth is the “Greats” part, and that, of course, is heavily subjective, with the average person probably considering it the worst thing they have ever heard.

But between the title, and the incredibly cheerful and cheesy photograph used for the album cover, it certainly appears convincing to someone not paying close enough attention, and its become a collective joke among Industrial enthusiasts, picturing the confusion and terror of anyone exposed to the album through this deception.

But beyond its function as a somewhat juvenile gag, this bait-and-switch is the most widely known example of what I like to call Interrogating the Format, a staple of early industrial works, and one that may still run through the genre’s DNA.

But to start, let’s define the term. When I refer to Interrogating the Format, I am talking about industrial artists tendency to take mundane, basic components of music formats and packaging, such as track lists, cover art, or the physical discs themselves, and incorporate them into the art itself in some way, often in ways that challenge the very nature of these components.

Throbbing Gristle: Establishing a Convention

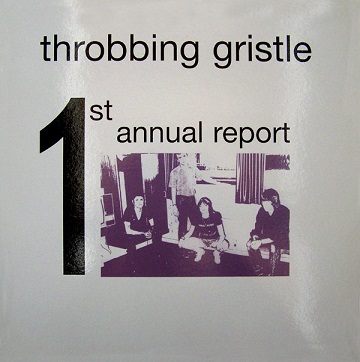

As the founder’s of the genre, it should come as no surprise that Throbbing Gristle’s body of work contains several examples of this, starting with their first official release, The Second Annual Report. The subversion in this title should be self evident; and in the days before the internet, there wasn’t any reliable way of finding out that there never was an original Annual Report, making this a very effective misdirection of people’s expectations.

Their follow-up release D.o.A: The Third and Final Report of Throbbing Gristle, played further into the deception, and included a twist of its own, the suggestion that this would be their final album. Eventually, a bootleg of early material was released as The First Annual Report, apparently feeding into people’s need to fill this numerical void and complete the sequence.

These misleading titles and the reactions to them demonstrate just how easily people can be manipulated by something as simple as a number on a record sleeve, and give reason to pause and consider how our demands and expectations can be preyed upon.

This wasn’t the only trick D.o.A was was home to, however. Someone checking the tracklist on the back would come away with the mistaken belief that the record would contain their (somewhat) poppy song “Unite”. True to form, however, this was another trick, and anyone purchasing the album for this reason would be disappointed to learn that, while the track is indeed present, it had been sped up by 15x, rendering it almost completely unrecognisable and comparatively unlistenable.

With D.o.A, Throbbing Gristle appeared to be displaying an almost unwavering contempt for anyone interested in singular tracks, as some pressings of the album spaced the track markers (visible grooves separating tracks, allowing the listener to skip to certain songs by dropping the needle into the correct place) out evenly across the disc, rendering them entirely useless for skipping to a certain track.

Considering that, in the last couple of decades, we have seen the rise of albums marketed off the backs of their singles (complete with stickers on CD cases informing you of what singles are included on each album), and multiple high-profile artists such as Pink Floyd ↗ and Garth Brooks ↗ objecting to their songs being made available for download independent of the original album, it would appear Throbbing Gristle were ahead of their time in attempting to start this conversation.

One final trick, came in a reissue of The Second Annual Report, this one by Fetish Records under the title “2nd Annual Report”. In at least one pressing ↗ of this reissue, the B-side was mastered backwards, rendering it more impenetrable than it had been originally. Intentional or not, it seems more than fitting for a band built off of these kind of deceptions.

New interpretations: Emergence of a Trope

Of course, one band, no matter how influential, cannot be taken as an example of a genre as a whole. While TG were out there attempting to prank the world, several other emerging industrialists took up the challenge to see how far they could twist these very basic conventions.

Formative industrial project NON made extensive use of these techniques on their EP Pagan Muzak. Upon opening the 12” sleeve, fans were greeted with a 7” record. To make matters worse, the B side was completely blank, making the album significantly shorter than its outside packaging would suggest. Instead, the vinyl comes with a second hole, drilled off-centre, with the implied suggestion that this constitutes double the music. Additionally, each track on the album featured a locked-groove, meaning the record will loop instead of skipping to the next track, necessitating the listener to sit by the player and reposition the needle after each track, in stark contrast to a more traditional release.

Cabaret Voltaire, who have long denied the industrial label, found themselves following in Throbbing Gristle’s footsteps with the release of their “Three Mantras” album. Those of you with an eye for pattern recognition can probably guess that there were in fact, not three mantras, rather two, one for each side of the record. Not content with just imitating Throbbing Gristle, however, they provided a unique twist in the labels on the centre of the record; both being identical, and thus providing no clue as to which side was which.

CV didn’t stop there, and in a later album attacked the idea of album identification itself with their double vinyl, 45rpm release 2x45, with the title serving as an objective, emotionless description of the record’s contents. This release also lacked any accompanying artwork, packaged only in a black sleeve, vying to create as featureless a package as possible.

Next, we have the band best known as Foetus, who opted to challenge the very convention of consistent band naming, and thus adopted a different moniker on almost every release for their first ten years of existence, and several more later on. Names adopted by the project included “You’ve got Foetus on your Breath”, “Philip and His Foetus Vibrations”, “Foetus Over Frisco”, “Foetus Über Frisco”, “Scraping Foetus Off the Wheel”, “Foetus Art Terrorism”, “The Foetus All-Nude Revue”, “Foetus Corruptus”, “Foetus in Excelsis Corruptus Deluxe”, “Foetus Inc”, “Foetus Corp”, “Foetus And The Transvestites From Hell”, “Foetus in your Bed”, “Foetus Under Glass”, “Jim Foetus”, and “The Foetus of Excellence”. Cataloguing these records must have been an absolute nightmare.

Finally we get to Thunder Perfect Mind, the title of two records released on the 28th of July, 1992, one by Current 93, and one by Nurse With Wound. Current 93’s album was named thus after a poem (lyrics from which appear on the album), and Steven Stapleton, of NWW, was compelled to name his after a dream he had. In the dream, he named his upcoming album Thunder Perfect Mind, before handing it to C93 frontman David Tibet. When David was informed of the dream, he agreed that both albums should share the title. While both very different musically, both albums feature Steven and David in some capacity, and are considered sister albums.

Public Transmission: Adoption outside of Industrial

Of course, all this creative energy couldn’t remain isolated forever, and plenty of non-industrial artists started getting in on the act, especially those from adjacent scenes, such as post-punk.

A great example is Durutti Column, who packaged their album “The Return of the Durutti Column” in a sleeve wrapped in sandpaper, causing damage to any other albums it was placed next to, and requiring it being stored and treated differently than your other records.

At the other side of the world, TISM released their single “Defecate on My Face” which, as well as being a 7” packaged in a 12” sleeve, also had the sleeve sealed on all sides, meaning it was impossible to get to without ripping the packaging, forcing would-be listeners to grapple with their desire for an undamaged sleeve vs actually playing their new purchase.

One of the more mainstream bands on this list, The Flaming Lips, went out of their way to create an album that was notoriously difficult to play with their 1997 release “Zaireeka”, which came on four CDs designed to be played at the same time on four separate players. The idea was that the placement, volume, and quality of the four players would ultimately create a unique mix for each person listening to it, and challenged pretty much everyone’s preconception of how an album could be mastered and played back.

And then we have “Jack The Tab – Acid Tablets Volume One” a supposed compilation of acid house tracks by various artists, but was in-fact an album by Psychic TV, with each track being given the name of a fictional band. Psychic TV, of course, was the brainchild of ex-Throbbing Gristle front-man Genesis P-Orridge, on his life-long quest to make the public question absolutely everything.

Dilution: Industrial’s assimilation into the mainstream

As the 90s rolled on, post-industrial found itself in the limelight as the “hot new thing”, and with this slew of new bands came new attempts at Interrogating the Format. What makes these notable is that, even so far removed from the original scene in terms of time, geography (most of the new breed being American rather than British), and ideology, this particular tradition continued. It is as though Interrogating the Format was built into the genre’s DNA, and had successfully passed on to its offspring.

One can’t talk about mainstream post-industrial without mentioning Trent Reznor and Nine Inch Nails, and their Broken EP gives us a fun example of them Interrogating the Format, with the CD apparently containing 99 tracks (the maximum possible value). Most of these consisted of a few seconds of silence, and were used to space things out before the “hidden” track at the end, but to someone placing the CD in the player for the first time, the display may have looked quite alarming.

A more subtle example could also be found on their album “The Fragile” with the two discs being labelled as “Disc Left” and “Disc Right” rather than the more traditional 1 and 2. Given that Reznor has stated that the album is a concept that loops, with it ending right back where it begins, this could be read as an attempt to let the listener choose their own starting point, rather than just beginning at disc 1. For someone whose industrial credentials are often brought into question, these examples help shine a light on how connected Trent is to the scene.

One of the lesser-celebrated, but still highly influential labels of the decade, Reconstriction Records, released a sampler of some of their big hits as the “10th Anniversary Collection”. It should go without saying at this stage that it wasn’t the label’s 10th anniversary (it was only their 5th).

Plunderphonics group Negativland gained notoriety from the release of their album “U2”, but one of their more intriguing acts came in the labelling of their album “Dispepsi”. Out of fear of being sued by a certain soda giant, they scrambled the name into a number of anagrams, using Eisdispp on the CD and Ipsdesip on the back of the case, whereas for the front, they had the letters all spread out as a collage, with the effect that most people were unsure as to what the album was actually called! On the inside of the case, there was a phone number you could call to be told the actual name of the album, but this will have been little help to those trying to mark the release up for store shelves!

Speaking of messing up labelling systems, Filter’s 1999 release “Title of Record” must have lead to a few double-takes from label staff and catalogue printers alike, with the name looking more like a spreadsheet error than an actual title.

Leading out of the decade, we have Hate Dept, who across multiple releases showed an interest in exploring an under-utilised source of artistry, their album barcodes. Starting with “Technical Difficulties” where they integrated the barcode into the rear album cover, stretching and fading it into the composition, they progressed into making it the main artwork for their follow-up “Ditch”. Not only is the barcode the sole focus of the back of Ditch, taking up almost a quarter of the space, just to make sure that nobody missed it, they also incorporated the album’s barcode into the band logo, which was the only element of the front cover, being displayed on a plain white field.

Lest you think they were going to stop there, their best of “House That Hate Built” also features stretched barcodes across the back cover, inner booklet and both discs, with the bars stretching out into patterns reminiscent of circuit boards. For a tiny element that most people wouldn’t give a second glance to, Hate Dept really wanted you to think about their barcodes, and in turn, focus on the blending of art and corporate product.

Ancestors: Interrogation in the 21st Century

Since the industrial bubble burst and the genre went back underground, this desire to Interrogate the Format appears to have died down significantly, and seems to be completely absent from some derivative subgenres, such as Future Pop. It certainly feels like, as far as those genres are concerned, Interrogating the Format has hit a genetic dead end, and is unlikely to re-emerge later down the line.

On the other hand, all hope is not lost. The subgenre known has Witch House appears to have developed a curious convention, wherein band names are often made up of obscure and unpronounceable Ascii symbols, such as “|††”, “§§§§#1”, “M‡яc▲ll▲”, and “†‡†” (the last of which is pronounced Ritualz, apparently). While the stated reason is apparently to make bands harder to find, and forcibly keep the scene underground, I can’t help but look at it as another step in an ongoing experiment. When you have a band name no-one can say out loud, can’t easily search for, and would certainly struggle to fit into an alphabetical system, these bands do seem to be asking “what is the purpose of a band name?”

Finally, we have the likes of Jack White and his label Third Man Records, who appears to be on a life-long quest to deconstruct how records can be arranged and packaged. Releases on Third Man often require setting players to odd (and sometimes even impossible) speeds, playing from the inner rim outwards, splitting records open to access smaller singles encased within or tearing off the centre label to reveal an additional track. As with a few other artists mentioned, whether his goal is to challenge audiences and make them question the nature of music and art, or simply to release some fun merchandise celebrating vinyl, is up to some debate, and highlights the challenge in not only identifying this convention at work, but also the inherent classification difficulties at the heart of industrial.

Almost from the beginning, it has been the case that what makes music “industrial” or not is often less about the sound, but the intention of the artist. Likewise, what separates Interrogating the Format from gimmicky pranks and messing around is an express desire to shake the foundations of these conventions, and confront audiences with the results.

With the trend seemingly dropping off in recent years, it would be interesting to see what, if anything, the future holds for this key part of Industrial music history, especially as we approach the genre’s 50th anniversary.

«Back to "Writing"»